- Home

- V. S. Alexander

The Irishman's Daughter Page 34

The Irishman's Daughter Read online

Page 34

She sighed and rested her head in her hands while trying to think of a solution. Not to be undone by Lucinda’s threat, she formed a plan of her own. She remained at breakfast until after her sister left for the Carlisles’. Then she took a warm bath, got dressed, and walked to work. The day was windy with grayish clouds that stretched over the city like a curtain. Her unborn child kicked on nearly every step she took during her brief walk to the office. She rubbed her tender abdomen and wiped the sweat from her face. A few steps later she was chilled to the bone by the breeze.

Mr. Peters was behind his oak desk at the rear of the building when she arrived. She tapped on his door, and he waved her in. He directed her to sit in the chair across from him. A lamp burned on his desk, shedding some light in an otherwise somber room with no windows. The floor-to-ceiling bookcases crammed with architectural plans and business ledgers exacerbated an already oppressive space. Briana was glad she worked near the front of the building, where some light entered through a small window.

“Were you able to hire a man to stand watch?” she asked after she had seated herself.

“Yes, and before you ask, I’ve already talked to my wife about what we might do to help Quinlin.” He cleared his throat and leaned back in his chair. “I don’t usually discuss such matters with my staff, but knowing the severity of the situation and having a soft spot in my heart . . .”

Joy filled her despite the sunless office. “Thank you, Mr. Peters.”

He waved a finger in the air. “Let me caution you—my wife and I can’t adopt the boy. We’re much too old for that.”

She was flabbergasted because she had never thought of asking him to adopt Quinlin. “Oh, no. I only wanted to ask if you could board him for a few days until I can get my sister used to the idea of fulfilling Addy’s wish.” She wondered if Rory would object to her adding a family member. There was no way to know.

“This is your sister . . . Lucinda?”

Once again, he surprised her. “How do you know my sister’s name?”

“Through a man we both know—Declan Coleman.”

Of course, it made sense that Declan, who got her the job, would tell Mr. Peters of their history and situation. “I only asked because Lucinda is so protective of me—sometimes too much so.”

“In some ways, Boston is a small town,” he continued, “particularly within the Irish community.” He picked up a pencil and twirled it between his fingers. “So you wish to save this boy and, I take it, your sister may not have the same feeling.”

He understood perfectly. “We’d have to find a place to live other than the boarding house. We’ve been so busy with our new jobs, we haven’t had time to look for other housing; in fact, Lucinda found out only recently that a room we had planned on taking at the Carlisles’ didn’t work out. In fact, we’ve considered moving in with Mr. Coleman. He asked us when we arrived in Boston if we might want to board in a spare room.”

He straightened, his black suit accentuating the appearance of a stern figure. “So, how do we solve this problem? The workday has begun, but I could be convinced to leave my desk for a few hours to rescue a child.”

Briana rose from her chair, overjoyed by his offer. “I’ll take you there.”

“You may lead me, but you will remain outside as I search for the boy. Let’s think of your child as well as Quinlin.”

She wanted to kiss the man who was behaving toward her like a protective father. She doubted that even her own father would have been as understanding as Mr. Peters. She rubbed her stomach—the baby seemed more settled now—then buttoned her coat and led the way out the door.

As they snaked their way through the crowded streets, Briana spotted the man she had encountered the previous month. Smoking a cigar, Romero Esperanza stood watching them from his position on an opposite corner.

She tugged on Mr. Peters’s coat sleeve, and he looked her way. “Do you know that man—the one in the coat and round hat with the broad brim?” She cocked her head to the right.

“I’ve seen him but never had the pleasure of his acquaintance,” he said, and clucked his lips in a disapproving manner. “Nor would any woman who values herself.”

“He offered to hire me, but I declined.”

“You were wise to refuse his offer.” He glanced over his shoulder at Esperanza. “Look at him—dressed in that expensive overcoat and gambler’s hat. Smoking a cigar on the street. Ha! From that alone you can surmise he’s devoid of any moral fiber. I can tell you that there is an element in Boston that works for evil. They try to dress it up, but their business is the business of rogues. The farther away he is from you, the better.”

Briana took a last look back at the man, who continued to gaze at them. She shivered and thought of Addy’s connection to the Carson brothers. She wondered if there was a connection between the brothers and Esperanza because of the man’s shady dealings.

Soon they were in the narrow lane that led to Addy’s house. Mr. Peters put on a brave face, but Briana could tell that he was appalled by the derelict condition of the homes, the drunks who slept in the doorways and small alleys, and the disgusting smell of the slops.

“Wait here,” he told her when they arrived at the door. The same old woman whom Briana had seen before answered Mr. Peters’s knock. The putrid odor of the house washed over them—a noxious mixture of unwashed flesh, excrement, and rotten food.

“What do you want?” the old woman asked in Irish. She picked at one watery eye and then dragged a finger through her gray, matted hair.

Mr. Peters looked at Briana expectantly.

“We’re here to pick up Quinlin Gallagher,” Briana replied in her native tongue.

The woman attempted a smile, but her snaggletoothed grin turned it to a sneer. “The lazy, good-for-nothing boy is down below, sleeping like he usually does. He played sick for a while, but he’s as healthy as a horse, the little beggar. He cried this morning because his mother hadn’t come home.” She spat on the step. “In her line of work, she didn’t come home plenty of times. You’d think the brat would be used to it by now.”

“What is she saying?” Mr. Peters asked, his patience with the old woman running thin.

“She said Quinlin is a wonderful boy and she would be happy if he were taken to a good home.” She blushed a little from her lie, but there was no need to upset her employer with a literal translation.

“Then let’s get to it,” Mr. Peters said, pushing toward the door.

The woman stopped him with her arm. “What’s this about? Is he from the police?”

“No,” Briana said, “he’s Quinlin’s . . . uncle. Addy Gallagher is dead.”

The woman spat again, this time at Briana’s feet. “Ha! She got what she deserved. Uncle, my ass. He doesn’t even speak Irish. I don’t care who he is as long as he’s not from the police. I’ve got enough trouble in this house. He’d do me a favor taking the boy away. Without a mother, he’ll be out on the street.”

Briana gestured toward the door. “Go ahead,” she said to Mr. Peters. “This lovely woman will take you to him.”

Mr. Peters pursed his lips and squinted into the darkness, his face twisted with trepidation.

The door closed, and Briana turned to watch the parade of people winding their way down the street. Women carried baskets of laundry tucked under their arms. Where they were going to wash clothes, Briana wasn’t sure. A few grubby children rolled the remains of a fractured wagon wheel up the muddy byway. After hearing the children’s excited laughter, she looked down at her belly and imagined her own child playing with other boys and girls—but not in these conditions. Would her child play in Ireland along the cliffs above Lear House? America had food, but so many times she had longed for her native land. A few men also passed by, but they seemed defeated, as broken as the children’s wagon wheel as they trudged along with haggard, bearded faces. Had liquor overtaken them, or was it America—a country not as welcoming as they had imagined?

The door cr

eaked open behind her.

Mr. Peters stood with a handkerchief clutched over his nose while a pale Quinlin shivered in front of him, clutching a muslin bag tied together with a topknot. The old woman hovered behind them. Mr. Peters ushered Quinlin down the steps to the lane, lifted the handkerchief from his nose, and replaced it in his pocket. “I’ve never seen anything so disgusting,” he complained, and gulped in deep breaths of fresh air.

The old woman laughed as if she understood his words, then said in Irish, “Glad to be rid of the brat. He carries that rag with him everywhere.” She closed the door in their faces.

“He’ll spend the day with me at the office, and when I get him home, he’ll get a good scrubbing in a hot bath,” Mr. Peters said.

“He may not like it.” Briana studied Quinlin, who stood as lethargic and defeated as the men she had seen earlier. She wanted to tell him about his mother but doubted her own strength to do so considering the boy’s condition. A painful stab of pity and sorrow cut through her. “Do you mind if I take the rest of the day off?” she asked her employer. “I need to clear things with my sister.”

He placed his hands on Quinlin’s shoulders. “Please do. I’ll see you tomorrow. Let’s not go into details until after he’s had a chance to settle in tonight.”

“Of course—I think that’s best,” Briana said, relieved by the delay of telling the boy about his mother’s murder.

They walked back on the same route, even spotting Esperanza speaking with two women in a carriage a block from where he had been. Once again, he followed them with his gaze.

“A most disagreeable chap,” Mr. Peters commented.

When they reached the office, Briana knelt before Quinlin and said in Irish, “Please mind Mr. Peters. He’s a good man, and he’s going to make your life much better.”

The boy, his ragged clothes stretched across his thin body, asked, “When is my mother coming to get me?” His pale blue eyes flickered under his tousled red hair.

“We’ll see,” she said, holding back tears.

The boy brushed his sleeve over his face. “Something bad has happened—I know it. When my father died, Ma told me that bad things happen.”

“We’ll talk tomorrow. I promise.” She got to her feet and blew a kiss to Quinlin. “Please mind Mr. Peters.”

The boy gave a shy nod and looked down at the bricks underneath his feet.

A profound sadness darkened Mr. Peters’s face as he opened the door. “Come inside, my dear boy,” he said. “Come inside.”

* * *

Lucinda wanted to hear none of it.

She might as well have been a stone wall, Briana decided.

“We can’t afford to keep him,” her sister kept repeating as they got ready for bed. “Besides, we’ll have to uproot our lives.”

“Uproot?” she asked incredulously. Her sister wasn’t resisting a move; after all, Lucinda had considered moving in with the Colemans. Quinlin, she was certain, was the point of contention. “We have a few bags to pack. They’ve offered their spare room, and I’m sure it will be reasonably priced. You’ve a good hand with boys; after all, you’ve worked with three of them for two years.”

“Yes, my good hand extends to their bottoms if they get out of line.” Her sister continued to sputter about money and the “inconvenience to the family.”

Briana turned out the lamp. “You’ll feel better about it in the morning.”

“I will not.” Lucinda crawled into bed and pulled the blanket over her head, unwilling to discuss the matter further.

* * *

Bright sunlight streamed in their window the next morning, but the oak floor was cold on their feet.

At breakfast, Lucinda continued her silence, brushing off any overture to discuss Quinlin.

She waited a few minutes after her sister had left for work and then put on her coat. She had never seen such a brilliant blue sky—a sign of cold New England air. As she walked to the building trades office, Briana wondered if other arrangements might have to be made for the boy. Perhaps Mr. Peters would know a kind family who wouldn’t mind taking in the child. Otherwise, as the old woman said, he would be condemned to a life on the streets, or end up in an orphanage. She blanched at the thought.

Mr. Peters was already in his office when she arrived. She hooked her coat on the rack and made her way through the dim hall. As usual, his desk lamp cast a yellow glow across his face. He smiled when she tapped on his open door.

“Come in, come in,” he said in a cheerful voice. “It’s a wonderful day.”

Briana was less enthusiastic about the morning, and failed to return his smile.

“No luck?” he asked, ascertaining the cause of her displeasure.

“She wouldn’t discuss it.”

Mr. Peters opened the center drawer of his desk and pulled out an envelope. “Perhaps this will change your sister’s mind.” He pushed it across to her.

Her fingers brushed against the paper. She was unsure whether to open it.

“Go ahead,” he urged.

The thick envelope weighed heavily in her hands. She opened the flap and gasped. It was filled with bank notes and silver.

“Don’t bother to count it,” Mr. Peters said. “Slightly more than two hundred dollars in currency and coin.”

Briana closed the flap and pushed it back across the desk. “Your generosity overwhelms me—but I can’t accept this.”

“It’s not a gift from me. The money belongs to the boy.”

“What?” She slumped in the chair, astounded by the news.

“The ‘rag’ he carried with him all the time held it—a hidden money box of sorts,” he said. “I did manage to get out of him—in broken English—that his mother had saved it. As far as I can work it out, they were planning to go to Pennsylvania to live with her husband’s brother, who is working on the railroad.” He lowered his gaze. “That would lead me to believe the murder might have something to do with this money.”

She believed he was correct in his assumption. If Addy was holding back money and the Carson brothers found out about it, they would come after her. After all, she had seen the threat with her own eyes. It made sense; still, she felt it unnecessary to disclose Addy’s occupation to her employer. He had probably guessed anyway.

“How is Quinlin?”

“He seems a fine boy, in decent health, thanks to you. He’s over what seems to have ailed him, and he mentioned you by name. A shy lad, but eager to learn, I think. He spent half the night looking at Audubon’s Birds of America.” He clasped his hands and looked at her with sadness. “He needs to be told about his mother.”

Sadness coursed through her.

“My wife is bringing him here this afternoon. Perhaps you can tell him then.”

The time would never be right, but she knew Mr. Peters was correct. The sooner the boy knew the truth about his mother, the sooner he could grieve and heal. More than ever, she needed Lucinda to agree to take in the child.

* * *

Briana fidgeted through her work, barely able to concentrate on the tasks before her. A short time after two in the afternoon, Mrs. Peters, fashionably attired in a high-necked cream silk dress and accompanied by a young servant girl, accompanied the boy to the office. They exchanged a few pleasantries before the woman turned him over to her.

Quinlin, still pasty white from his months of living in the cellar, squirmed in his new set of breeches, shirt, and jacket. The blue coat accentuated his pale complexion and red hair. Briana led him to a quiet room adjacent to Mr. Peters’s office, where they both took a seat. A grimy window threw a murky light into the room.

The boy wasted no time in asking, “Where is my mother, and what happened to our money?”

The bluntness of his question startled her—it seemed a world-wise inquiry from a child of five or six, as she had judged the first day she met him. “How old are you?” she asked.

“My mother gave me the bag on the ship for my seventh birthday.” His ey

es narrowed. “She told me to keep it by my side, for it holds a treasure. Where is it?”

“Your money is safe,” Briana said, surprised at his age. “Mr. Peters, who fed and clothed you last night, removed it while you were asleep and placed it in an—”

“My mother told me there was more than two hundred dollars!”

She leaned forward and grasped his hands, a lump rising in her throat. “This is so hard for me to say, Quinlin . . . but your mother isn’t coming back.” She paused, studying his face and holding back tears. “Your mother’s dead.”

He stared at her; then his tears began to flow, silently, in large drops down his face. The boy registered no other emotion except a sob, and he withdrew his hands from hers. He looked beyond the door, into the hallway, and said, “I don’t want to go back to that house.”

“You won’t have to,” Briana said. “I promise.” She wiped a tear from her own eye and thought of Lucinda working at the Carlisles’ only a few blocks away. If only her sister could see the boy now, trying to act so grown-up in the face of his mother’s death. How could she make her sister understand that Addy Gallagher was a mother who wanted the best for her son, just as their father wanted the best for them?

Mr. Peters knocked on the door and entered with the envelope. “I wanted him to see this,” he told her. “I can keep it in the company safe until you need it. I imagine he wants to know where his money went.”

“He’s already asked,” Briana said, and handed it to Quinlin so he could inspect it. The boy opened the flap and thumbed through the bills with a slight smile, as if the money was his personal friend. He then closed it and watched them as they conversed in English.

“I’ll talk to my sister this evening,” she continued. “We have to save—despite this money—still, I see no reason to stay at the boarding house. It’ll be more of a walk to work from South Cove, but the exercise will do me good. Can he stay a few more nights with you, at least until I can get the room straightened out?” She looked up at the kind face of her employer, who stood as stiff as a bog oak plank.

The Irishman's Daughter

The Irishman's Daughter The Sculptress

The Sculptress The Taster

The Taster Her Hidden Life

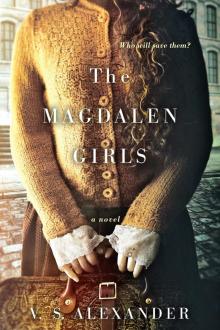

Her Hidden Life The Magdalen Girls

The Magdalen Girls