- Home

- V. S. Alexander

The Irishman's Daughter Page 2

The Irishman's Daughter Read online

Page 2

She tightened her mother’s red shawl about her shoulders, covering her nose and mouth. The faint odor of wisteria water, a gift long ago from her father to her mother, blotted out the terrible stench.

She walked in the center of the pebbled lane, avoiding the carriage ruts carved into the path, lifting the hem of her scarlet petticoats as she bounded over puddles. An excursion up or down the drive was always a challenge by carriage. Often she preferred to be let out on the hilltop road to walk down to the house, even in the foulest weather. The middle of the path also held its dangers—rocks dislodged by the horses, indentations made by the power of hooves, that could easily cause a sprained ankle or fall.

The estate was separated by irregular lines of brush and stone fences, some hundreds of years old and others built much later as the tenant population bore children and expanded its claim. Many of the homes had thatched roofs, but most were little more than mud huts with a vent so the turf-fire smoke could escape. The estate seemed to grow every month with a new fence and the wail of a newborn.

Soon she neared Rory’s small acreage where he tended his potato crop, in addition to the oats and rye he farmed on land higher up the hill. He sold the oats and rye, as did the other tenants, to pay in kind for his rent. The lane led her past the larger parcels, some as sizeable as an acre, down to the quarter acres owned by Rory and his brother.

Rory leaned casually against the corner of his cabin. He was clad in dark breeches, a white shirt, and a green jacket; he, like her, wore no shoes. Tobacco smoke twirled through his nose and mouth as he inhaled deeply from his clay pipe. His reddish hair glowed auburn in the sunset. Near his cabin, a pig snuffled in the turf. Rory, like other tenants, kept the animal inside at night for safety and warmth.

She stopped a few paces away, her body kept to a respectable distance by the social views of her father. “A woman should save herself until her marriage night,” he had told her years after her mother had died. His words only echoed those she was sure her mother would have spoken had she lived. Tonight, the plans she dreamed of sharing with Rory, the whispered words of love she wanted to say, would wait for another day. No matter that they had known each other since they were children and their affection had grown over the years. The time to show it hardly ever seemed to present itself because of their duties with the manor and farm. But their marriage was coming soon. Rory had told her so.

Rory pointed to the potato ridges that weren’t far up the sloping land.

She stared at the blackened leaves and pressed the shawl tighter against her mouth.

Rory beckoned her closer, stooped, and touched one of the dark leaves. It melted into a viscous goo in his hand. “See,” he said, “this is what the poet predicted would happen. Look.” He grabbed a nearby spade and thrust it into the ground. He dug quickly, turning over the moist earth at the top of the ridge. The potatoes were planted there for maximum drainage. He reached into the earth, grasped the potatoes and lifted them for her to see.

He crushed one with his hand, and a slimy mush dripped from his fingers. His hand opened in the feeble light, revealing the moldy, black and gray meat inside them, gangrenous in appearance.

She would never have suspected that the crop, lush, bright and green as of yesterday, could change to rot in less than a day. She stepped back. “Are they all gone?”

“All that I’ve checked,” Rory answered. He threw the rotten potatoes on the ground and rubbed his hand across the furrow to rid his fingers of the putrefaction. “Even my pig has the sense not to touch them.”

“The ‘plague’ Daniel Quinn predicted. And we don’t know why?”

Rory nodded. “The summer was mild and wet, excellent for growing potatoes. Even the fall has been good. Some will say this curse came from rain and wind, others insects, but what I fear most are those who will claim it comes from God.”

“Even after Daniel Quinn departed, Father said it was silly to worry about such things,” Briana said. “ ‘Providence will provide, ’ he told me.”

The wooden door to Rory’s brother’s cabin creaked open. Jarlath stretched his arms, lit his pipe and then nodded to Briana. She shifted on her feet and bowed slightly to him.

Looking back to Rory, Briana asked, “Is every row like this?”

“Yes, this crop is ruined. We’ll have to start over for the spring. I don’t know whether we can salvage seed potatoes.”

The poet’s words about the “plague” came rushing back to her. A number of horrifying thoughts struck her as she stared at the plants, including one that crept slowly in from the back of her mind, of not having enough to eat—starvation, plainly put. All the farmers, even her family, depended upon the potato for their daily meals. To lose the crop would mean they would have only seed potatoes to eat, and those wouldn’t last forever. A disturbing picture flashed through her mind as she imagined children begging for food as they lifted their empty bowls.

“What will the people eat. . . . What will we eat?”

Rory looked toward the gray waves of Broadhaven Bay. “Maybe a herring, if Jarlath can fish the waters. Seaweed? Birds’ eggs? A frog now and then.” He chuckled at the thought.

Briana didn’t think his musings were funny. Few men ventured out in their small canoes, their curraghs, on the ragged ocean, and they knew the risks when they did. She had seen the bodies of several drowned men. The ocean currents were powerful, the tides swift, the waves treacherous on most days, and only the most skilled among them could navigate the Atlantic waters.

Rory looked again at the rotted plants lying putrid on the ridges, and his voice turned somber. “Without food, the people won’t have the strength to farm. How will we pay the rent if we have to eat our oats and rye?”

Briana hadn’t thought that far ahead, and his question jolted her. “I don’t know,” she said after a few moments. “The crops have to be sold.” She wanted a solution, but the immensity of what she had seen was too much to take in. “I have to tell Father,” she said, and walked toward the lane. “He doesn’t even know—he’s been working inside all day.”

Rory followed a few steps behind. “Will I see you tomorrow?” he asked in a wistful voice.

She turned, well aware that they both would have liked to have met under more pleasant circumstances. “Tomorrow.”

He took her in his arms and kissed her. She didn’t mind that Jarlath, still outside smoking his pipe, was a witness, for he would never speak of their affection to her father. Besides, everyone on Lear House grounds knew, or at least suspected, that one day they would be married.

She left him standing at his cabin. The deepening indigo sky retained its swaths of red. The wind licked against her, and she folded her arms against her chest. Fear lapped at her as well, as the images of the rotted plants floated through her mind. Only one question offered some hope. Was there anything her father could do? She was filled with doubt. In less than an hour, her world had shifted.

Rinroe Point beckoned, with its broad view of the ever-shifting Atlantic, but the walk was long and treacherous at night. Sitting by the cliffs, watching the stars shift in and out of the clouds, would be so much easier than telling her father about what she had seen.

He might be reading in his chair near the turf fire or, by now, have fallen asleep. The cottage would be cozy and warm inside. “You saw Rory, didn’t you?” she imagined he would ask with slight disdain. “You can do better.” It wasn’t that he didn’t like or respect Rory, or perhaps hold some love for him in his heart—but she understood that her father, in his love, wished for her a better life than a tenant farmer might have to offer. A life like her sister, Lucinda, might construct.

She arrived at the circular lane in front of Lear House. The house was as black as her mood. No light burned in any window, and the ivy clung like strangling, dark fingers over the stone face.

She shivered and darted toward the cottage door.

Her father had read King Lear to her years before. He loved Shakespeare and had

imparted that love to his daughters. The playwright was one of the reasons he had learned English and then taught the language to Lucinda and to her.

She thought of Rory and how much she longed to be with him as she clutched the latch. Lines from the play came into her head.

So we’ll live, and pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too . . .

Any sense of happiness of singing and telling tales was blotted out as she thought about the crop. Without potatoes there would be nothing to eat. Her father would be placed in the difficult position of collecting rents he couldn’t gather. And she knew from his bookkeeping troubles that many of the tenants were already in arrears. This failure would put them further in debt.

A hopeful thought struck her as she stood outside. She would write to Lucinda informing her of the blight and ask her to intercede with Sir Thomas on the family’s behalf as well as the tenants’. Those words, asking for forgiveness of debt, might fall upon the unsympathetic ears of the landlord, but it was the best plan she could think of. Her sister, after all, was in close contact with the Englishman through the family she worked for.

She decided not to tell her father of her scheme. Of course he would raise a strong objection to her interference in a business matter. It would be better if he didn’t know.

Her mind shifted back to Rory and the crop failure and then to her family’s situation. What of the food stored in Lear House? How long would it last? The questions made her head spin.

She stepped inside and greeted her father, who looked up from his reading, closed his book, and smiled.

Her stomach quivered as she spoke. “I saw Rory this evening.”

His smile faded into a look of thoughtful reflection. “I thought you must be with him. It took you longer than usual to check on the house.” The light from the oil lamps and the turf fire cast flickering shadows across the room. Her father lowered the book to the floor.

“You’ve not been outside today, have you?” she asked.

“Other than to run from Lear House to the cottage,” he replied. “Why?”

“Did you smell it in the air?”

His nose crinkled. “What? I noticed nothing unusual. The wind was strong off the bay.”

That explained it. The wind would have swept the odor up the hill toward the farms and then on toward the village of Carrowteige. It had now shifted more from the Atlantic. “The potato crop has failed—rotted.”

Her father smiled again, as if she had told him some kind of perverse joke. “We’ve been through these before—it can’t be as bad as you imagine.”

Briana sat in a chair across from him. “Rory says all the ridges have failed. There’s nothing left. Daniel Quinn told us it would happen.”

He scoffed. “The poet isn’t right about everything. I’ll check in the morning. Now I’m going to bed.” He rose from his chair.

“Perhaps Sir Thomas should be notified that the tenants may fall into more debt,” she said without mentioning her plan.

Her father turned, his face flushed. “I would never do such a thing!” He lifted his book and tossed it on the chair. “I’m working very hard to keep Lear House solvent. Sir Thomas need not be burdened with an additional worry.” He started for his bed and then stopped. “And don’t get any grand ideas in your head. You should stay out of my business, and that includes any meddling from Rory Caulfield.”

“Well, you’ve made your feelings clear.” Briana got up. “I’m headed to bed as well.”

“Daughter,” Brian said with a tone of reconciliation, “let’s not panic. The tenants have had many troubles over the years, and this is one more—that we will get through together.”

She admired her father for not panicking despite the stress he was under. She kissed him on the forehead and retired to her room as he extinguished the oil lamps. The cottage still glowed from the smoldering turf fire.

Despite what her father instructed, she couldn’t let go of her plan to write Lucinda. What could it hurt? It would be a friendly note to her sister with one addition.... She undressed and said her prayers. She was grateful for the firelight because it made her feel that she and Lear House were safe—at least for the moment.

CHAPTER 2

April 1846

“By all that’s blessed in heaven, I don’t know what we’re going to do,” Brian Walsh said as he peered out the drawing room window of Lear House. He threw back the curtains, sending a stream of dust whirling into the air.

She was getting taller, or her father was shrinking. But the crop failure, the threat of starvation, the necessity to collect rents from families they had known for years—many of them friends—had taken a toll on him since October. He was forty-two but looked older. Deep creases lined his cheeks, and his forehead was furrowed with ridges. His gray hair fell in wild wisps from his temples, while the top of his head, lacking in locks, reflected the light shining on his balding pate. Briana worried about his health and what the situation in Mayo was doing to his constitution. He spent long hours over the ledger books, muttering to himself, thinking about ways to keep Lear House from falling into bankruptcy.

Her father swiped at the air, scattering the dust in the breeze. Even the suspenders that pulled at his breeches couldn’t correct the slight stoop in his posture.

Briana wiped the black smudges off a silver candlestick and then removed the dust covers from three high-backed chairs. She was excited at the prospect of reuniting with her older sister. Lucinda’s arrival was a celebration of sorts, yet her feelings were tempered by the harsh realities surrounding Lear House. Her father, despite his troubles, had insisted on opening the drawing room to his oldest daughter. He was taking liberties that wouldn’t be afforded others, and he was only doing it for Lucinda, whom Briana suspected had come to expect such treatment.

Briana threw her polishing rag upon the sideboard as her anger toward Sir Thomas rose to the surface. Her letter asking for a temporary exemption from debt had been ignored. The only posts she and her father had received in the months since October had been those of salutations and greetings from Lucinda, talking of the dull English weather and offering holiday cheer.

The long-time cook and hired man had been dismissed early in the year as a result of Blakely’s wishes. The Englishman’s reasons, as her father had reported them, had been vague as far as Briana was concerned, but her father had not raised a fuss, preferring to remain silent and accepting of Blakely’s opaque explanation rather than risk their own livelihoods.

“I don’t want you to think you’re a serving girl,” her father said as he paced in light made dull by rain. “You do enough now, but we’ll all have to do more if times don’t change.”

Briana appreciated his concern, but he depended upon her housekeeping now that the help had been dismissed. For years she had helped Margaret in the kitchen and even assisted Edmond when needed. Lucinda was too concerned with her books and studying to learn how to cook a proper meal—her culinary skills were only enough to keep her alive. Briana supposed her sister longed for the day when cooks and maids would be preparing and serving her food.

Drops from the misty clouds splattered the window.

“Where is the damn carriage?” Brian pushed a hand through the few strands of hair that remained on top of his head.

“Probably delayed by weather,” Briana replied. “I can’t imagine the terrible shape of the road from Belmullet after the winter we’ve had.” Lucinda was sailing into the port village on a ship from Liverpool, the passage paid for by Sir Thomas. The carriage journey to Lear House was many miles from the port—but one that could be accomplished in much less than a day in good weather. Briana knew her sister had no affinity for arriving at the small store on Broadhaven Bay that sold goods. The ships landing there were small and uncomfortable.

Her father turned a chair toward the window and took a seat. Briana stoo

d behind him and looked out upon the wide lawn. Through the mist she could see the store far below.

“I wouldn’t have believed the crop could be destroyed had I not seen it with my own eyes,” Brian said. He rubbed his palms together and formed a steeple with his fingers. His hands were hardened into strong instruments of work, tight flesh, sinew and bone, molded by long hours in the fields before Sir Thomas had hired him as agent.

Briana put her hands on his shoulders. “No need to worry, Da. Everything will work out.” No sooner had the words left her lips than she doubted their truth. They had a hollow ring, a platitude that anyone could express. No sentiment could blunt the dread that filled people now. Rumors had spread through the tenant farms of evictions, homes destroyed, whole families living in holes in the earth, their only protection being a crude roof of branches and sod. Rory had told her of “ejectment” atrocities in Galway. Her stomach had churned when she’d heard these stories because she knew they were true.

She preferred to remember the happier days of growing up in the cottage, on the grounds surrounding Lear House. Carefree, taking in the wonders of life—Briana had sparred with her older sister but grew close to her father after her mother had died. She had learned to milk goats, at first afraid to pull the teats but then getting her hands upon them, as practiced as any milkmaid. She fed livestock, collected water from the spring, and learned how to cook. Markets, fairs, and county celebrations made up her life. And there was Rory, whom she admired for his strong spirit and handsome face and body. Their friendship, which turned to courtship over the years, had filled the sparse time they could find together with walks along the bay, along the cliffs, reveling in all that nature had to offer. Rory had stolen several kisses at Rinroe Point when she was fifteen and he was sixteen. The innocent act had taken her breath away, and the feeling of his lips upon hers had lingered for days, leaving her cheeks flushed and her hands tingling.

On the other hand, her sister had, over the years, stretched out in the cottage during the winter and on the grass in summer, content to read textbooks on various subjects and romantic novels, and dream of a life far away from Mayo. Her father spent what little spare time he had watching sporting races and fights. He had even sparred once, much to the consternation of Briana and her sister. Both cried when he took them to the makeshift ring in the village. He left victorious, but with a broken and bloody nose.

The Irishman's Daughter

The Irishman's Daughter The Sculptress

The Sculptress The Taster

The Taster Her Hidden Life

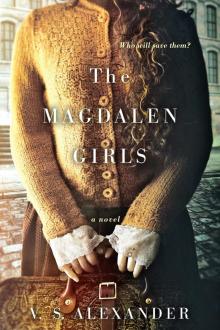

Her Hidden Life The Magdalen Girls

The Magdalen Girls